I never liked discipleship programs. And by inference, I’ve always had a kind of revulsion for the idea of discipleship. At least at a visceral level. Intellectually I know that Jesus called us to make disciples (Matthew 28:19-20). In fact, the Great Commission does not send us out to make converts; it specifically charges us with making disciples. There is an assumption in the teaching of Jesus that anyone who becomes a convert will also be a disciple.

I have known all of this for almost as long as I’ve been a Christian. Yet in spite of it, I feel repulsed by the idea of a discipleship program. This is the first time I’ve ever publicly acknowledged this feeling. It just doesn’t sound like the sort of thing anyone who wants to be considered a reputable Bible teacher would admit.

Studying the word for “disciple” recently, I believe I have identified the reason for my strong feelings on the subject and I have become reconciled, even excited, about being a disciple.

One reason is that I have seen tremendous abuse of the concept. In my experience (and that of others I have known) “discipleship,” as a formalized program, means appointing church leaders to spend time with a select group of followers and teach them how they should live a disciplined Christian life.

I don’t deny that many have benefited from such an arrangement, and if you are one of those, I am glad, and nothing in this post should be taken as criticism of your growth. But a couple of problems are built into such programs.

First, there is an emphasis on teaching. Discipleship programs usually have curriculum attached. This frequently leads to a “do as I say, not as I do” kind of approach. The disciple-er, the Master or Teacher, often seems to think his role is to make others live up to certain standards, not to live up to them himself.

In fact, the maintenance of control usually extends through several layers of authority. In order to keep everyone in the program “safe,” the church leadership develops material for every disciple group to teach, all at the same time. That gives control over the teaching, but it also eliminates adaptation to the specific needs or learning abilities of the disciples themselves.

Second, I have often seen leaders of these groups use their position as a means to indulge a desire for status, prestige and power over others. The potential for discipleship to become abusive is off the charts. I realize my revulsion is in large part a result of seeing this abuse so frequently.

A third problem is that I’ve rarely seen any clear definition of what it means to be a disciple. Most teaching I’ve heard on the subject relates the term to discipline or being a disciplined follower of Jesus. “Discipline” usually means little more than regimented and regular prayer, Bible study and service of some sort within church. The actual definition is quite different.

I say all of this to put the study of this word into perspective, since I doubt most of you reading this have experience all that different from mine.

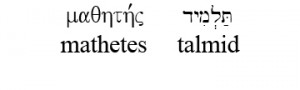

The Greek word for “disciple” is mathetes. It means “a learner, disciple, pupil; from math-, the mental effort needed to think something through.”

It’s Hebrew counterpart is talmid, and of course, when we define “disciple” in the context of the ministry of Jesus, the Hebrew has greater relevance, since the twelve apostles started out as talmidim of Rabbi Jesus. Talmid means “a pupil or scholar; based on the root lamad, to teach.”

Thus it is correct to think of a disciple as a student or learner. However, the practical application of that concept in Hebrew culture was somewhat different than the Greek or Western concept that we generally assume. I quote here from notes given me by Pamala Denise Smith of Gateview Ministries. She has succinctly and clearly delineated the difference:

“While talmidim is translated from Hebrew as ‘disciples,’ the Greek mindset of discipleship relates knowledge to how we should live; whereas, the Hebrew Roots basis of being His talmidim turns living experientially into gained knowledge.”

In other words, Jesus didn’t lecture his disciples about how to live. He invited them to experience life with him, providing in his own life, behavior and attitudes a model for them to copy, thus making the experience itself their teacher.

This idea of imitation was at the core of Jewish discipleship. The student learned more by imitating his teacher than he did by simply listening. The importance of imitation is illustrated in the life of Hillel, one of the most famous Jewish rabbis in the first century. Hillel purposely mispronounced a particular word. When asked why, he replied, “I know that I mispronounced it, but that is the way my Rebbi spoke!” (Eduyos 1:3). (There could be a lesson here about being careful who you imitate. Better be sure they have it right.)

Disciple, by definition, is a student who learns by practice. A disciple in the culture of the first followers of Jesus was someone who intentionally imitated him until they not only acted like him but thought like him.

This suggests a couple of thoughts about fulfilling the Great Commission, that is, making disciples:

First, we are not called to get people to imitate us. We are to invite people to join us in striving to imitate Jesus. He is the real rabbi, the true teacher. We are all in learning mode together. Discipleship does not work well under a hierarchical structure where one learner has power over another. Discipleship is a much more egalitarian practice, in which all of us, both new believers and mature, are practitioners walking together.

Second, though getting people to be our disciples is not the goal, we need to be aware that any of us who enter into leadership in any capacity will find others beginning to imitate us. Our goal is not to teach people information as much as it is to become something worth imitating. That way they can see Jesus in us and strive to imitate those characteristics until they learn to imitate him directly on their own. This is why Hebrews 13:7 tells us, in regard to our leaders, to consider the outcome of their way of life, and to imitate their faith. It is also why Paul could tell the Corinthians, “Be imitators of me, just as I also am of Christ.” (1 Corinthians 11:1).

This leads to a couple of questions we must ask ourselves:

- Are we imitating Jesus or are we hiding behind doctrine to give the appearance of spirituality without having to actually grow or change?

- Are we in the process of becoming something worth imitating?

I am in total agreement with you. There are folks being trained as ‘disciples’ who have not the knowledge or gift to be true imitators of Christ.

Just think how different church would be and how much more influence it would have on society if we got this one thing right. Imagine a world where Christians actually did consistently imitate Christ. Mmmm.